[cmsms_row][cmsms_column data_width=”1/1″][cmsms_text animation_delay=”0″]

Sacramento Bee September 28, 2014

Sacramento Bee September 28, 2014

By Dale Kasler

dkasler@sacbee.com

It’s harvest time in much of California, and the signs of drought are almost as abundant as the fruits and nuts and vegetables.

One commodity after another is feeling the impact of the state’s epic water shortage. The great Sacramento Valley rice crop, served in sushi restaurants nationwide and exported to Asia, will be smaller than usual. Fewer grapes will be available to produce California’s world-class wines, and the citrus groves of the San Joaquin Valley are producing fewer oranges. There is less hay and corn for the state’s dairy cows, and the pistachio harvest is expected to shrink.

Even the state’s mighty almond business, which has become a powerhouse in recent years, is coming in smaller than expected. That’s particularly troubling to the thousands of farmers who sacrificed other crops in order to keep their almond orchards watered.

While many crops have yet to be harvested, it’s clear that the drought has carved a significant hole in the economy of rural California. Farm income is down, so is

employment, and Thursday’s rain showers did little to change the equation.

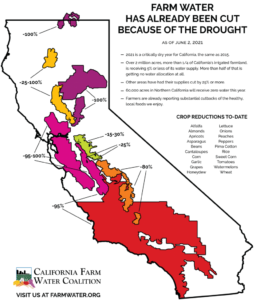

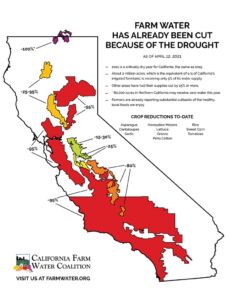

An estimated 420,000 acres of farmland went unplanted this year, or about 5 percent of the total. Economists at UC Davis say agriculture, which has been a $44 billion-a-year business in California, will suffer revenue losses and higher water costs – a financial hit totaling $2.2 billion this year.

Rising commodity prices have helped cushion at least some of the pain, but more hurt could be on the way. With rivers running low and groundwater overtaxed, the situation could get far worse if heavy rains don’t come this winter.

“Nobody has any idea how disastrous it’s going to be,” said Mike Wade of the California Farm Water Coalition, an advocacy group based in Sacramento. “Is it going to create more fallowed land? Absolutely. Is it going to create more groundwater problems? Absolutely.

“Another dry year, we don’t know what the result is going to be, but it’s not going to be good,” Wade said.

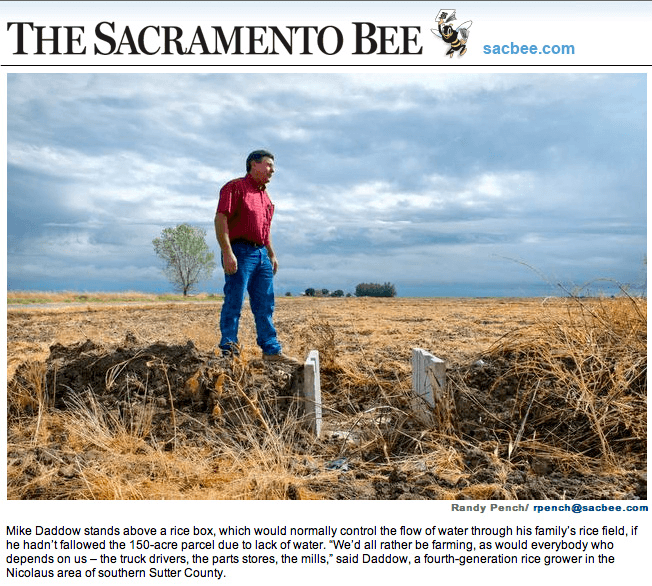

Sacramentans don’t have to look far to see the effects. Roughly one-fourth of California’s rice fields went fallow this year, about 140,000 acres worth, according to the California Rice Commission, leaving vast stretches of the Sacramento Valley brown instead of their customary green.

“We’d all rather be farming, as would everybody who depends on us – the truck drivers, the parts stores, the mills,” said Mike Daddow, a fourth-generation rice grower in the Nicolaus area of southern Sutter County.

Daddow opted to fallow 150 of his family’s 800 acres this year and counts himself lucky. “We did better than a lot of people,” he said.

Last week, Daddow was gearing up for the harvest, which begins Monday. It was pleasantly warm, but the faint smoky smell from the King fire was another unwelcome reminder of the parched season of discontent.

“It affects me, yes, I will have less profit,” he said. “It affects hourly workers. If there’s no ground to till, I can’t hire them to do anything.”

Daddow hired just six workers during spring planting, instead of the usual nine or 10.

Three Boxes, Not Two

Calculating total job losses related to the drought is difficult, especially in an industry in which many workers are transient and much of the work is part time. The state Employment Development Department, drawing from payroll data, said farm employment has dropped by just 2,700 jobs from a year ago, a decline of less than 1 percent. But experts at UC Davis say they believe the impact is more severe. Richard Howitt, professor emeritus of agricultural economics, said he believes the drought ultimately will erase 17,000 jobs. He bases that, in part, on the increased number of families seeking social services.

The human cost shows up at rural food banks, which are reporting higher demand for assistance from farmworkers and their families. At the Bethel Spanish Assembly of God, a church in the Tulare County city of Farmersville, the number of families receiving food aid every two weeks has jumped from about 40 last year to more than 200. Farmersville, a city of 10,000, is at the heart of a region that grows an array of crops, from lemons to pistachios to grapes.

“Some of them are working … but they’re not putting in the hours,” said the Rev. Leonel Benavides, who is also Farmersville’s mayor. Thanks to state-funded drought relief, the church has been able to meet the increased demand – and then some.

“Instead of just two boxes, we give them three,” Benavides said.

The effect goes beyond the farm fields. N&S Tractor, which sells Case IH brand farm equipment throughout the Central Valley, has seen business tail off as farmers conserve cash.

“It’s not just our dealership,” said N&S marketing director Tim McConiga Jr., who works out of the company’s sales office in Glenn County. “You talk to John Deere, you talk to Caterpillar, everyone is going to tell you their numbers are down.”

The drought has had varying impacts on different areas of the state, depending in part on who has first dibs on the dwindling water supply. Some growers have stronger water rights than others. Generally speaking, Sacramento Valley farmers have had it easier than their counterparts south of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, where the cutbacks have been more severe.

Regardless of geography, many growers have had to make difficult choices about which fields to water, leaving portions of their farms idle.

Bruce Rominger of Winters, chairman of the California Tomato Growers Association, made the decision to push ahead with his tomato crop at the expense of other commodities. With tomatoes selling for a robust $83 a ton, vs. about $70 a year ago, it was a matter of simple economics.

“Other crops are not getting the water,” said Rominger, who owns and leases a total of about 5,000 acres. “We sacrificed some alfalfa, we sacrified some sunflowers, we sacrificed quite a bit of rice. We fallowed 25 percent of our farm.”

Almonds, Citrus Affected

Choosing to focus on one crop doesn’t guarantee victory. Even the $4 billion almond industry – the great success story of California agriculture in recent years – could not be shielded from the drought’s effects.

As worldwide demand for almonds has boomed, prices have soared past $4 a pound and farmers have responded with more supply. Orchard plantings have continued unabated, even this year. With water supplies running low, many almond growers set aside other commodities to keep their orchards going.

Even so, the almond yield declined. Blue Diamond Growers, the big farmer-owner almond cooperative based in Sacramento, predicts that production in California will fall this year to around 1.9 billion pounds when the harvest is complete in a few weeks. That compares with the 2 billion pounds harvested last year and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s forecast, released in late June, that this year’s crop would total 2.1 billion pounds.

What went wrong? Almonds are one of the thirstiest crops around, and there wasn’t enough water to generate big yields.

“I don’t think there was anyone who used as much (water) as they normally do,” said Dave Baker, director of member relations for Blue Diamond. The hot spells in June and July “stressed the trees even further” and curtailed production, he said.

With California accounting for 80 percent of global almond supply, Baker said he’s worried about being able to meet demand. “We have a growth industry,” he said.

The lack of water last spring likely also has stunted navel orange production in the San Joaquin Valley, where harvest is expected to begin in a few weeks.

“We’re expecting some kind of damage to the crop,” said Alyssa Houtby, spokeswoman for California Citrus Mutual, a grower-owned association based in Tulare County. “We didn’t have the water in those key months.”

Economist Vernon Crowder, a senior vice president with agricultural lender Rabobank, said farmers went into this difficult season with a couple of advantages: Most commodity prices have risen in recent years, and most growers are in pretty good financial shape as a result. But another dry year could bring more serious hardship, he said.

“They have a little bit of cash to withstand this,” Crowder said. “They’re going to get through it. The real question is what is going to happen next year.”

California Wine Industry

Similar questions are being raised in the California wine industry. The last two grape harvests were extraordinarily strong, leaving an overhang of product that should help offset the slight declines in this year’s harvest. “Pricing should be steady,” said industry consultant Robert Smiley, a professor emeritus of business at UC Davis.

That doesn’t eliminate fears that next season’s crop could shrink substantially. Craig Ledbetter of Vino Farms, a Lodi grape producer, had enough water this year but said he’s afraid he’ll receive “curtailment notices” from the state signaling significant cutbacks in next season’s water supply.

“I’m very nervous about water,” said Ledbetter, who also raises wine grapes in Sonoma County. “If we don’t have a rainy winter, I can pretty much guarantee we’re all going to be receiving curtailment notices. If that happens, we’re going to be concerned about keeping the vine alive rather than harvesting it.”

[/cmsms_text][cmsms_text animation_delay=”0″]

[gview file=”sacbee092814.pdf”]

[/cmsms_text][/cmsms_column][/cmsms_row]